|

One of the fundamental requirements for the

control of action within an environment is the ability to perceive

the layout of objects and surfaces. No single source of information

about the relative distances of objects and surfaces can provide

the information required to perceive layout throughout the range

of distances required. However, in cluttered

well lit conditions typical of natural environments people are

very good at obtaining information about layout through the simultaneous

use of multiple cues.

The relative effectiveness of different sources

of information differs systematically with the distance of objects

and surfaces from the observer, and also with characteristics

of the observer and the environment (such as the size of objects,

the speed which an observer is moving through the environment,

and the nature of the terrain).

Considerable research has been undertaken

to describe sources of distance information, and Cutting &

Vishton (1995) describe seven independent

sources, summarised below. A number of outstanding questions

remain, however, regarding how multiple cues are combined in

the perception of layout under different conditions.

Pictorial Cues

Occlusion. An

opaque object which hides, or partially obscures another object

provides ordinal information about the layout of objects in the

environment. Occlusion is an effective cue throughout the complete

visible range of distances.

An example of effective and ineffective occlusion cues. The

cue is not effective where the contour is unclear.

Relative size/relative density. The size of the retinal image projected by objects

of the same size differs at different distances (relative size),

and the density of the retinal images of regularly placed clusters

of objects, or textures also varies with distance of the objects

or textures from the observer (relative density). Relative size

and density can yield scaled information, and is effective over

the complete visible range of distances.

An example of relative size

. .

Examples of relative density

Height in the visual field. Ordinal information about the distance of the objects

is available from the vertical location in the visual field of

the bases of objects resting on the (horizontal) ground. The

bases of more distant objects are located higher in the visual

field than the bases of closer objects. Scaled information is

available relative to the observer's eye height. The cue is not

useful at very close distances, is maximally effective at distances

of about 2m, and decreases in effectiveness to a distance of

about 100 m.

Example of height in the visual field indicating

distance

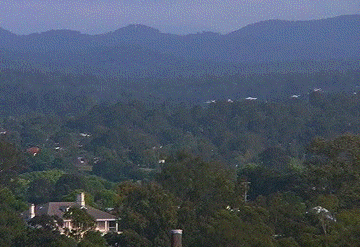

Aerial perspective.

Atmospheric interference causes distant objects to become bluer,

and decreased in contrast relative to nearer objects. The distance

over which the cue is effective varies with atmospheric conditions,

but increases in effectiveness from distances beyond 100m before

decreasing in effectiveness at distances beyond several kilometres.

An example of aerial perspective

Another example of aerial perspective, and one in which relative

size conflicts with the height in the visual field of the object

(power pole bases) indicating that the ground is sloping away

from the observer.

Motion cues

Motion perspective.

The apparent motion of objects caused by movement of the observer

through the environment provides information about the layout,

for example, near objects appear to move past a moving observer

more rapidly than far objects. Information is not available about

objects which are too close relative to the velocity of movement

to be tracked, and decreases in effectiveness to about 100 m,

again, depending on the velocity of movement (useful at greater

distances when velocity is high).

Motion perspective

Binocular cues

Convergence.

Maintaining single vision of proximal visual targets requires

the extra-ocular muscles of the eyes to rotate the visual axes

toward each other. Fixation of closer objects requires a greater

degree of convergence, and corresponding increase in the activation

of the extraocular muscles (medial recti) to achieve this convergence.

Information from the extra-ocular muscles regarding the degree

of vergence thus provides information about the distance of objects

from the observer. The cue is only effective at very small distances

(< 2 m). While changes in accommodation (the shape of the

lens) necessary to focus on objects has traditionally been accepted

as a second extraocular cue for distance, recent evidence suggests

that accommodation provides little, if any, useful information

(Tresilian & Mon-Williams, in press).

Vergence changes with distance

Binocular disparity.

The image of same object viewed through two eyes is projected

to different locations on the retinas of the eyes. The relative

position of the images provides information about the distance

of the object from the eyes. Disparity provides greatest information

for very close objects and decreases in effectiveness to about

10 m.

Summary

No single source of information about the

relative distances of objects and surfaces can provide the information

required to perceive layout throughout the range of distances

required. People are very good at obtaining

information about layout in the cluttered natural environement

through the simultaneous use of multiple cues.

However, even in tasks, such as endoscopy,

where available cues are reduced ingenious methods can be adopted

to provide the observer with the necessary layout information

(see Voorhorst,

1998).

The relative importance of each cue varies

with distance. For objects within personal space (< 2m) occlusion,

retinal disparity, relative size, convergence and motion perspective

provide useful information (in decreasing order of effectiveness).

For objects within action space (>2 < 30m) occlusion, height

in the visual field, binocular disparity, motion perspective

and relative size are useful; while for objects and surfaces

in vista space (> 30m) occlusion, height in the visual field,

relative size and aerial perspective cues provide the information

which allow actions to be controlled.

Required Reading

Cutting &

Vishton (1995)

|