|

Successful interactions between an observer

and the environment, and objects within the environment, implies

an knowledge of what actions are possible and appropriate in

any given situation. Gibson (1979) defined affordances

as the opportunities for action for the observer provided by

an environment, and proposed that observers perceive these affordances

rather than abstract physical properties of objects and environments.

In this sense affordances are real. They have

a relational ontology in they do not exist as a function of either

the environment or the observer alone, but only have existence

in the interaction between the physical capabilities and properties

of the observer and the physical properties of the environment.

For example a stair case of certain dimension may afford bipedal

locomotion by an adult, quadrupedal locomotion by an infant,

and a barrier to an observer confined to a wheelchair.

Affordances are likely to be both dichotomous

at critical points that correspond to transitions for behaviour,

and possess a preferred range corresponding to best fit between

environment and observers capabilities and characteristics. For

example, Warren (1994) demonstrated that

a critical ratio of riser height to leg length determined whether

a stair was climbable bipedally or not, and that a different

ratio corresponded to the most metabolic efficient riser height.

Further, observers were able to correctly distinguish climbable

and non-climbable stairs, as well as the metabolically optimal

riser height, from visual information. The perception of affordances

is likely to involve body-scaled metric rather than arbitary

metric, and it seems likely that eye height information is utilised

in the perception of affordances.

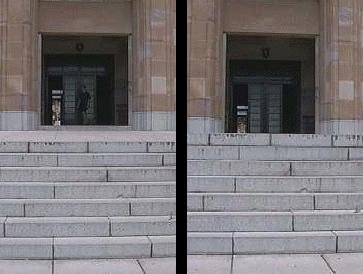

The same stair case viewed from different eye heights. Which

stair case looks harder to climb?

As we have seen in previous sections, the

optic array specifies relationships among layout of surfaces,

and the relationship of those surfaces to observer. The optic

array also provides information about self, including motion

of head/body and hands. While knowledge about an affordance such

as the climbability of a staircase could be determined through

a process of perceiving the height of the riser and comparing

this with a memory of the height of stairs which the observer

is capable of climbing, Gibson proposed that, in the same way

as local disturbances in the optic flow provided information

about events, higher order optical invariants provide information

about affordances.

For affordances to be perceived observers

must be sensitive to the information in the optic array; and

attend to that information. Attention is directed by intention,

so that, for example, a rock forming part of the supporting surface

may be ignored during locomotion, but attended to when a hammering

tool is required. Perception of affordances is influenced by

experiences, and can be learned.

Tools have dual functions tools as objects

contribute to the affordance of the environment. Before being

used, a tool has its own affordances, inviting certain actions.

Tools in use are no longer just objects, now they extend the

persons capabilites (effectivities) and become components of

the effectivity system. In complex situations affordances may

be nested. For example, a macadamia nut affords cracking and

eating, but only if an appropriate object which affords cracking

the nut can first be located.

Affordances are sometimes misperceived. The

baby approaching, but not crossing, the visual cliff (Gibson

& Walk, 1960) has misperceived the

affordance of the glass surface; and similarly, a pedestrian

who walks into a glass door has made a similar error. Such errors

are uncommon in the natural environment, but more common in fabricated

environments and objects. Indeed, the general challenge for designers

is to design environments and objects so that the affordances

are accurately and easily perceived with minimum learning.

Implications for design

The designer's task is more difficult than

an observer's. The designer must perceive the affordances of

a situation for others. The designer's task is often underestimated

because people are so proficient at judging affordances for themselves

that they fail to recognise the inherent difficulties in accurately

assessing the affordances for others.

The task is similar to that of an adult assessing

the affordances of an environment for a child in their care.

People are less accurate at perceiving the capabilities of others.

For example Zaff (1995) found that people

underestimated the height to which people shorter than them could

reach, but overestimated the height that taller people could

reach. The exception were experienced child care workers who

overestimated slightly the height to which shorter people could

reach, explaining "Little children can always reach higher

than it looks like they can".

Design is a process which requires simultaneously

taking into account the structural and dynamic properties of

individuals who will be using the product and the structural

and dynamic properties of the product.

The use of natural mappings between actions, and consequences

of actions, is likely to increases the ease of perception of

affordances.

The use of metaphors is a common design tactic

to convey information about affordances, but not always an effective

tactic. The necessity for the use of signs to indicate appropriate

action indicates a design in which the affordance is not easily

perceived, or in some cases where the affordances perceived is

not the action the designer intended. (see This

is a Mop Sink).

Required Reading

Gibson, 1979

Warren 1995

Norman, 1998

|